Siga @tucuman.art nas Redes

Prussian Blue: How Frankenstein Revolutionised the Art World

The colour blue, once highly prized in Ancient Egypt, was lost to the art world for centuries. That is, until a chemical accident at Frankenstein Castle led to the creation of the pigment that transformed modern art.

Johann Conrad Dippel, a theologian and anatomist, was born in 1673 at Frankenstein Castle, where he later worked as a professional alchemist. Some believe he may have inspired Mary Shelley’s imagination when she wrote her novel Frankenstein.

His time at the castle is shrouded in mystery and legend. Rumours circulated that Dippel exhumed corpses and conducted medical experiments in the hope of bringing them back to life. A local clergyman allegedly witnessed one of these experiments and reported to his parish that Dippel had created a monster, which came to life after being struck by lightning. Some even claimed that he signed the bodies with the name “Von Frankenstein”, despite having no relation to the family that gave the castle its name.

From a modern perspective, it is clear that many of these rumours and legends stemmed from the ongoing conflict between science and religion. At the time, the Church often viewed scientific advancements with suspicion. Due to his controversial views, Dippel was imprisoned on charges of heresy. Disillusioned with theology, he eventually turned his full attention to alchemy.

Putting aside the myths, Dippel’s most notable creation during his time at Frankenstein Castle was an animal-derived substance known as Dippel’s Oil, popularly referred to as the “Elixir of Life”. This dark, viscous liquid had such a foul taste and odour that, during the Second World War, it was used as a military strategy to contaminate drinking water, depriving enemy forces of hydration.

Dippel’s Oil was made by distilling decomposed horn, leather, ivory, and blood, to which Dippel added potassium carbonate.

The Accidental Discovery of Prussian Blue

Dippel shared his workspace at Frankenstein Castle with Johann Jacob Diesbach, a Swiss pigment and dye maker. One day, while preparing a batch of carmine red pigment using cochineal (a small parasitic insect from Mexico), Diesbach realised he was short of potassium carbonate. To compensate, he used a small amount of Dippel’s Oil.

The next day, he returned to his workshop to find something astonishing: instead of the expected red hue, he had produced a striking shade of blue. The substitution of potassium carbonate with Dippel’s Oil, which contained blood, triggered a complex chemical reaction involving the iron in haemoglobin, leading to the accidental discovery of this new pigment.

The Evolution of Blue and Its Impact on Art

For centuries, blue pigment had been scarce and expensive. In Ancient Egypt, it was widely used in art, but its primary source, azurite, was a rare and costly gemstone. Some artists managed to produce shades of blue by grinding turquoise or lapis lazuli (found in present-day Afghanistan), but these materials remained prohibitively expensive, making blue a symbol of wealth and exclusivity.

Recognising the value of this accidental discovery, Diesbach refined the pigment’s production with Dippel, making it more affordable and stable. Partnering with Johann Leonhard Frisch, they introduced the pigment to the world. Its composition and manufacturing process, however, remained a closely guarded secret until 1724.

In 1709, this new pigment was officially adopted as the colour of the Prussian Army’s uniforms, earning it the name Prussian Blue. It remained in use until the First World War, when the German military replaced it with Feldgrau (a grey-green shade).

The earliest known use of Prussian Blue in a painting can be seen today at the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam, in The Entombment of Christ (1709) by Adriaen van der Werff.

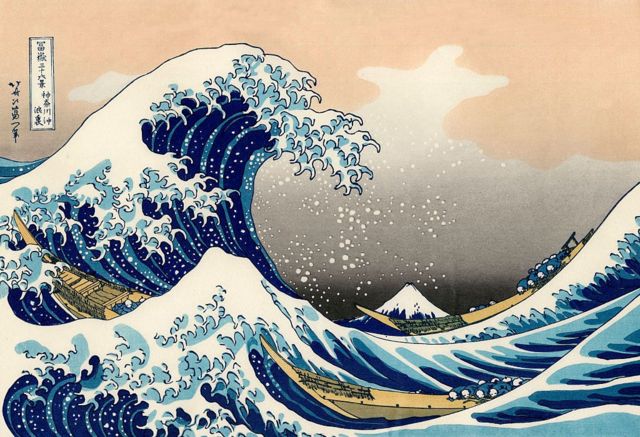

Over time, the pigment spread across the world. In 1831, it was imported in large quantities to Japan, where it was used extensively by artist Katsushika Hokusai in his iconic print The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

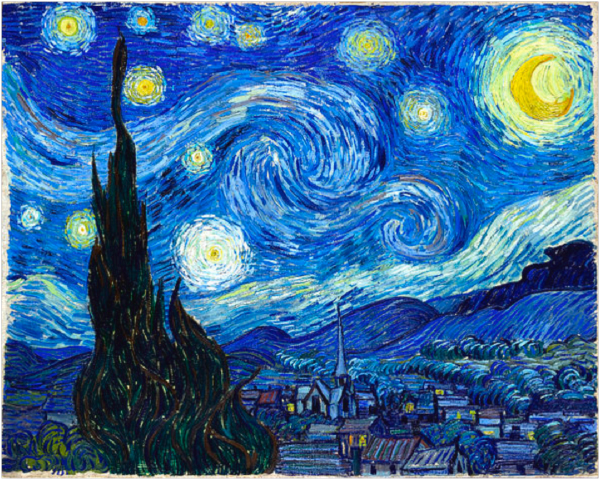

In the 20th century, Pablo Picasso made extensive use of Prussian Blue during his Blue Period, a phase marked by his depression following the death of his close friend Carlos Casagemas. One of his major influences during this period was Vincent van Gogh, who also used the pigment in works such as The Starry Night (1889).

Whether Johann Conrad Dippel truly had the ability to bring the dead back to life is difficult to say. But thanks to his elixir, the colour blue was reborn, forever changing the world of art.

Camila Vollger

Creative Director e Co-Founder na Tucuman Design Editorial, Camila Vollger sempre teve paixão por tecnologia, artes e fotografia. É formada em Comunicação e especialista em Produção Audiovisual pela ESPMRio. Sua área de atuação sempre foi mais voltada para criação publicitária e direção de arte tanto para mídias online quanto offline (gráfica).