Siga @tucuman.art nas Redes

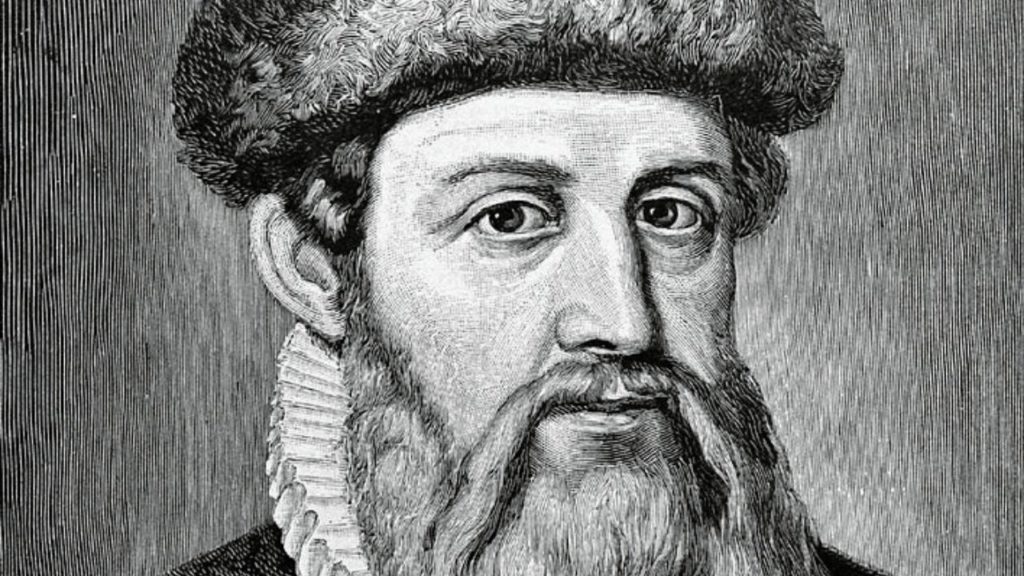

Gutenberg and the dawn of a new era

The invention of Gutenberg’s printing press sparked a revolution across numerous aspects of society, permanently altering its structure. It is widely regarded as one of the most significant inventions of the second millennium

As an adult, he spent much of his life in Strasbourg, on the border between France and Germany. It was there that he met Andreas Dritzehn, a successful businessman with whom he founded a partnership alongside two other associates. Their goal, however, remained a closely guarded secret.

This mysterious project left Dritzehn heavily in debt, and after his death from the plague at Christmas in 1438, his brothers filed a lawsuit against Gutenberg. Court records from the time mention “a secret art” and describe efforts to remove “the parts of the press (…) so that no one would know what it was.” Whatever the true nature of this project, the legal dispute was eventually settled, with the Dritzehn brothers receiving compensation. Gutenberg, as the principal partner, continued to invest his time and money into developing what we now know as the metal type printing system — an invention that would revolutionise the world and mark the dawn of the Modern Era. Today, it is considered the most important invention of the second millennium.

Printing Before Gutenberg

Although Gutenberg is often credited with inventing the movable-type printing press, the foundation of this technique had existed for nearly eight decades prior in Japan and China.

The origins of this method are believed to date back to the 8th century, when Bi Shēng, a Chinese artisan from the Song Dynasty, developed woodblock printing. However, despite serving a similar purpose, his method differed significantly from the one popularised by Gutenberg.

Shēng’s technique involved carving characters onto individual blocks of wood or clay — a process that was well suited for logographic writing systems with thousands of ideograms but was far less efficient for the phonetic alphabet used in Europe.

Additionally, Gutenberg’s system was far more advanced and efficient. His metal type had a major advantage over Shēng’s wooden characters: it was far more durable and absorbed less ink, making the printing process significantly faster and longer-lasting.

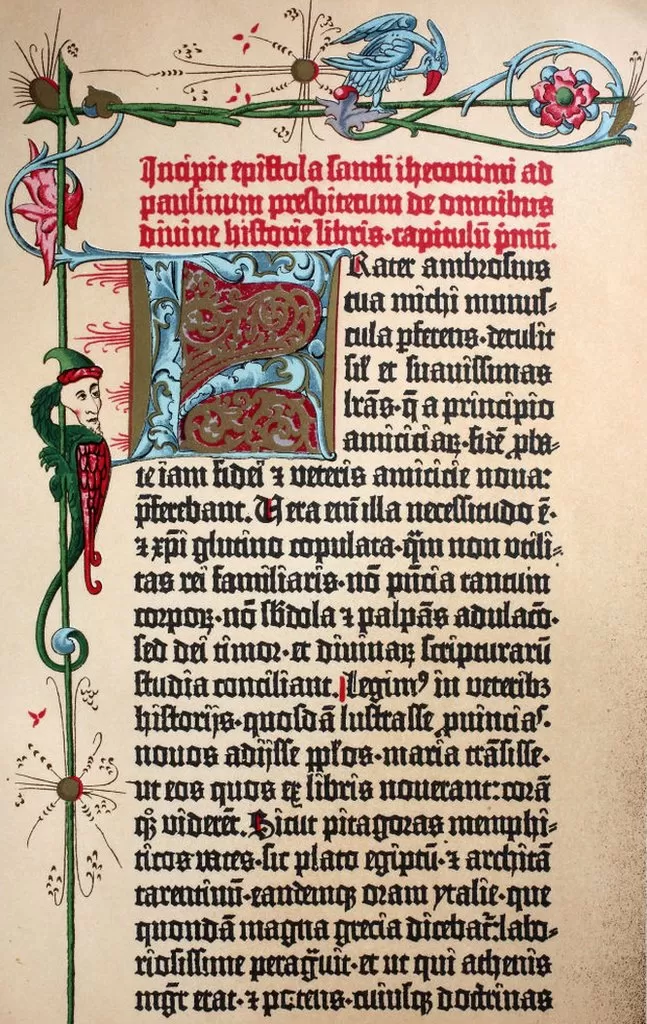

The Gutenberg Bible

The first book Gutenberg printed to test his press was a 28-page grammar book. However, his second project became his most renowned and celebrated achievement, a Latin Bible, printed in a beautifully detailed Gothic typeface and adorned with exquisite illustrations. This masterpiece became known as the Gutenberg Bible.

Consisting of 1,282 pages, arranged in two columns and spread across two volumes, the Gutenberg Bible amazed all who saw it with its remarkable craftsmanship and elegance. It was considered the most important incunabulum — a term used to describe the earliest printed books produced with movable type, as opposed to handwritten manuscripts and marked the beginning of a new era.

In 1455, when Enea Silvio Piccolomini (the future Pope Pius II) saw a copy of the Bible displayed in Frankfurt, he described Gutenberg as a “marvellous man” and noted that “the lettering was so clear that one could read it without glasses”.

Of course, not everyone welcomed this new invention. The arrival of the printing press caused great unease among scribes and monks, who feared that their traditional roles as manuscript copyists would become obsolete in the face of this revolutionary technology.

Before Gutenberg, books were extremely expensive, reserved only for the wealthiest individuals. Each copy took months to produce, as it had to be painstakingly handwritten by scribes and religious scholars.

The exact number of copies produced remains unknown. According to a letter written by Pope Pius II, there were approximately 180 copies, of which 45 were printed on parchment and 135 on paper. What is certain, however, is that every copy was sold before printing was even completed, a process that began in 1450 and concluded in 1455.

According to the British Library, only 48 copies of the Gutenberg Bible are known to exist today, though not all are complete — some survive only in fragments.

A Revolution That Shaped the World

Gutenberg’s invention sparked a revolution so profound that it permanently reshaped society. It played a crucial role in the Renaissance, the Protestant Reformation, the Printing Revolution, and the Scientific Revolution.

With Gutenberg’s printing system making mass book production possible, book prices plummeted and reading materials became widely accessible. A single book that once cost the equivalent of six months’ wages was, within a century, reduced to a fraction of that price — by the 17th century, a book could be purchased for as little as six hours’ pay.

This widespread accessibility to books triggered an explosion of ideas. In the first century following Gutenberg’s invention, more books were printed than had been manually copied throughout the entire history of Europe up until that point.

As more printed materials became available, literacy rates soared across the continent. Teachers and scholars gained increasing recognition, leading to an eightfold increase in teacher salaries with the rise of the printing press.

Scientists also embraced this new technology, using it to publish their theories and discoveries in academic journals, fueling the Scientific Revolution.

Yet, despite his groundbreaking invention, Gutenberg never became wealthy. He had been accumulating debt since his partnership with Dritzehn, and shortly after the success of the Gutenberg Bible, he faced yet another lawsuit — this time from another business partner — which resulted in him losing ownership of his own printing press.

Camila Vollger

Creative Director e Co-Founder na Tucuman Design Editorial, Camila Vollger sempre teve paixão por tecnologia, artes e fotografia. É formada em Comunicação e especialista em Produção Audiovisual pela ESPMRio. Sua área de atuação sempre foi mais voltada para criação publicitária e direção de arte tanto para mídias online quanto offline (gráfica).